|

Grant sets off across a "clearing" littered with deadfall after leaving the old campground road. |

|

Here is Chancellor Peak (left) as seen from the clearing. Alan Kane's ascent route initially follows the timbered ridge at right. |

|

Grant carefully walks on a downed log in the forest. |

|

Grant pauses for a moment while ascending the timbered ridge. |

|

Here is a view of the upper mountain from the timbered ridge. |

|

Grant continues to climb the timbered ridge on bits of rudimentary trail. |

|

This convenient gully on the timbered ridge is largely free of deadfall. |

|

Near tree line, Grant wanders to climber's left to find an access route to the upper mountain. |

|

Grant scrambles up the access route to the upper mountain. |

|

Grant traverses over to another gully (not the main ascent gully) en route to the upper mountain. |

|

The loose rocks in this gully are very tedious to ascend. |

|

Grant descends a very loose and steep chute in order to traverse to the main ascent gully. |

|

Grant enters the main ascent gully. |

|

Grant is about to pass under a snow bridge at the foot of a waterfall. |

|

In this view from under the snow bridge, Grant climbs up a very steep section next to the waterfall. |

|

Grant follows the snow patches in the upper part of the main ascent gully. The route eventually heads to the left and ascends steep slabs. |

If the first 2000+ metres of this mountain had not already done so, the final section before the summit definitely earns Chancellor Peak its Kane rating as a difficult climbers' scramble. After dropping my gear, I scrambled up the path of least resistance and was quite pleased to discover a ledge system which gained height from climber's right to left. I eventually emerged onto a vast airy face of down-sloping slabs and loose rocks. Considering how slow I was ascending, I was a little shocked when I spotted Grant still climbing directly above me. He had wandered a little too far to climber's right and was floundering in some very steep terrain. At some point, he even tossed his poles away for good--at least in his mind--in order to make better use of his hands! Somehow, the fact that I was catching up to him a bit reinvigorated me, and I held out hope that I could still make the summit. Instead of following Grant, I tried to steer more to climber's left aiming for what appeared to be a gully just below the summit. Grant had acknowledged my presence by now and was apologetic about sending a few rocks bouncing past me. Knowing that he already had his hands full with where he was scrambling, I told Grant not to worry and reassured him that I would remain vigilant for more rocks coming down. Of course, I had my own challenges with the terrain I was climbing and was not always alert as I had promised. In particular, I was busy working my way up a crack when I heard a rock whiz by me much too late. Before I even had a chance to react, another rock hit me squarely on top of my helmet. Fortunately, the rock that hit me was not big enough to knock me off balance, but I shudder to think what might have happened had it struck me in the face.

I eventually lost sight of Grant again and presumed that he had made it to the summit. As it turned out, I was only about 15 minutes behind him, and as I reached the gully below the summit, Grant popped back into sight above me and gave me an encouraging cheer as I grovelled up the remaining few metres to the top.

|

This is a foreshortened view of down-sloping slabs below the summit (left). The best route heads left of the outlier that Grant (blue jacket) is currently muddling under. |

Sonny stands on the summit of Chancellor Peak (3266 metres).

|

Mount Vaux and Hanbury Glacier dominate the view to the north. Note the high tarn under Hanbury Glacier. |

|

The view to the northeast includes many of the big mountains in the Lake Louise area. |

Grant holds up two summit register containers. At left are The Goodsirs.

|

Sonny and Grant take a selfie on the summit of Chancellor Peak. |

|

Grant begins the long descent. |

|

Grant takes advantage of a lingering snow patch to glissade and rapidly lose elevation. |

|

Grant prepares to down-climb the dauntingly steep section above the snow bridge and next to the waterfall. Note the increased flow in the waterfall. |

Where we began deviating from the GPS up-track, we only had about 1.4 kilometres to go to reach the edge of the decommissioned section of Hoodoo Creek Campground, but we still had some 600 metres of elevation to lose. Losing these 600 metres would prove to be painfully slow because the bushwhacking through this stretch would be the worst of the entire trip. Toothpick deadfall covered nearly every square metre of ground here, and there was simply no respite from the incredibly tedious maneuvering through endless tangles of logs. More than once, I slipped while walking on a log and fell awkwardly into a mess of nasty undergrowth. After one of these slips, Grant noticed that I had a lot of blood on my right pant leg. I was certain that it was just a minor scratch, but when I inspected the hole in my pants, I noticed a big flap of skin hanging loose with a huge divot in my right leg just below the kneecap. Oddly enough, I did not feel too much pain, but I was also likely in shock. Grant immediately performed first aid by wrapping a couple of shirts around my leg to stop the bleeding. Fortunately, I had not broken any bones and was still mobile, and once I was patched up, we continued grinding through the thick bush.

Grant took the lead after my injury, and he made every effort to ease my suffering by holding back or breaking branches, pointing out potential hazards, or giving me words of encouragement. A recurring mantra for us was that going down or losing elevation was good, but we just seemed to be doing it so slowly. The hours passed by, and it was disheartening to look up every once in awhile and see the headlights on the Trans-Canada Highway still well below us. Dehydrated and exhausted, I felt like lying down and sleeping countless times, but Grant kept us moving steadily through the bush. Somewhere along the way, my ice axe slipped from my pack, and Grant would have lost his too if I had not been following behind him. At one point, we entered what seemed like a promising drainage, but it too proved to be a bushwhacking nightmare. Admittedly, despair began to creep into my tired mind.

The forest seemed like it would never end, but ultimately it did. In the wee hours of the morning, we emerged into the scrubby clearing we had crossed the previous day. Although there was still some difficult ground to cover, we were finally free of the nasty toothpick deadfall. We eventually stumbled onto the same road we had started the trip on, and our suffering was finally at an end. Twenty minutes later, we were back at my car guzzling refreshments from our coolers. When we were sufficiently re-hydrated, Grant drove me to Mineral Springs Hospital in Banff, Alberta where I spent about four hours having my laceration repaired (24 stitches).

I want to thank the emergency medical staff at Mineral Springs Hospital in Banff for their excellent work and professionalism. I owe a huge debt of gratitude to Grant Myers for his patience, understanding and mental toughness. I would probably still be in that hell-hole of a forest if it was not for him. Thank you, Grant!

|

At the Banff Mineral Springs Hospital, Sonny's severe laceration from a slip while bushwhacking in the dark is revealed in all its glory. |

|

Sonny leaves the hospital after getting 24 stitches and a splint to immobilize his leg. |

|

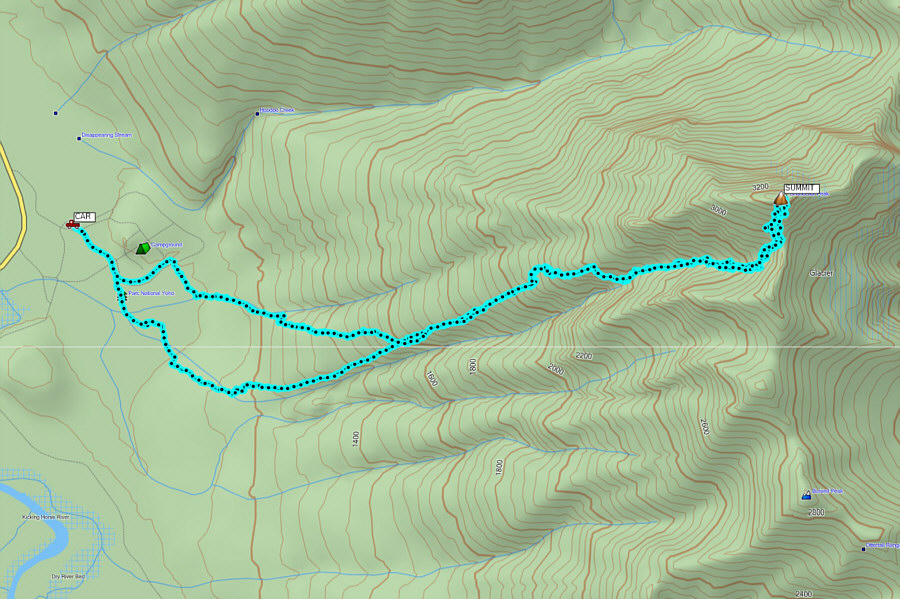

Total

Distance: 20.5 kilometres Round-Trip Time: 23 hours 43 minutes Net Elevation Gain: 2234 metres |